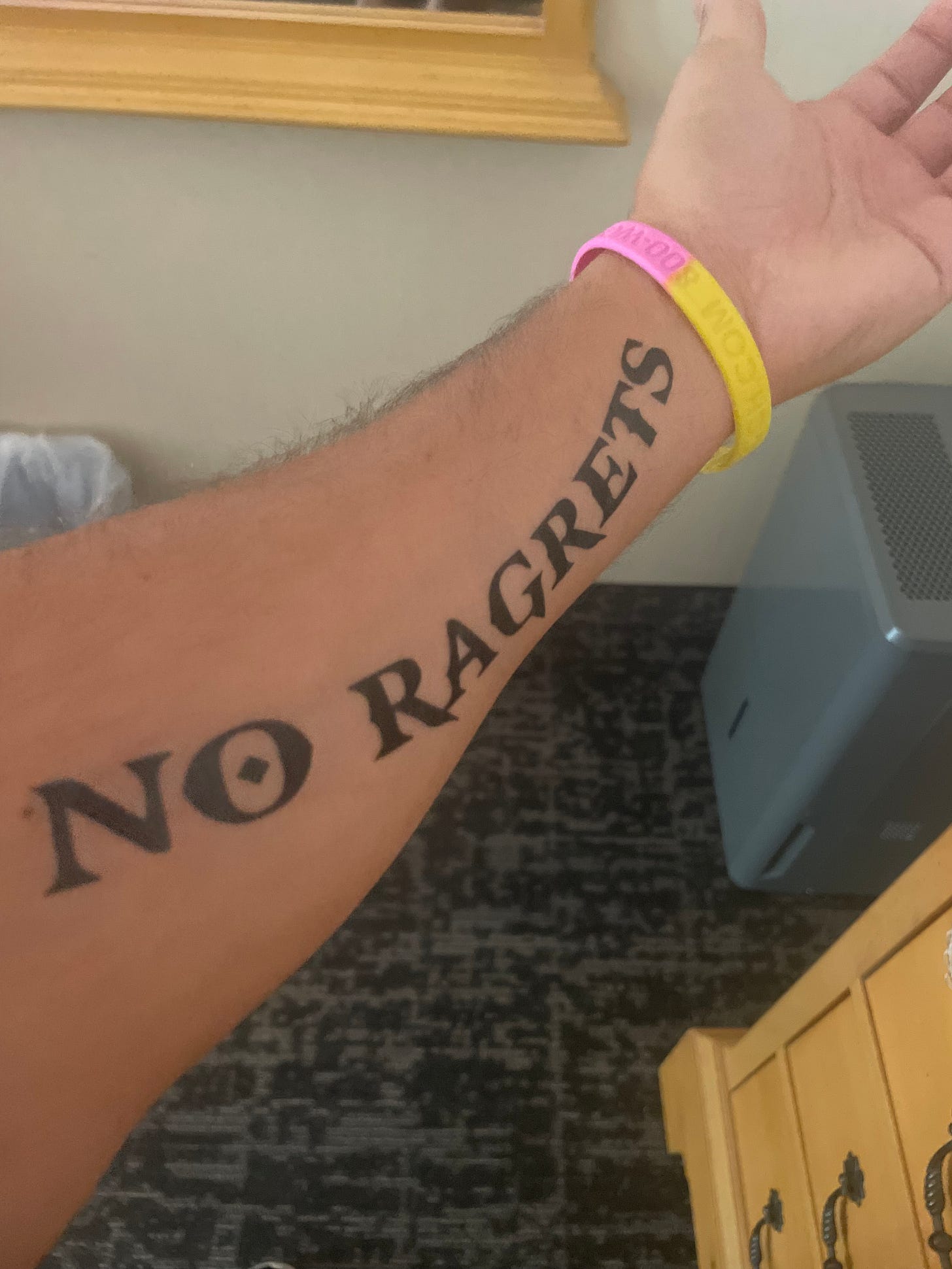

RATLINKS: NO RAGRETS

How My Family Paid $3,200 to Shoot Bigfoot in the Dick and Discovered the Last Place in America Where Vulnerability is Mandatory

Sammy's hands, and this detail will matter later the way small details always matter when you're trying to understand how ordinary Americans have managed to transform the basic human capacity for affection into a billable service, are dealing out twenties with the practiced indifference of someone who's watched forty-one summers' worth of families try to purchase what their grandparents got for free. The bills whisper against humid Pennsylvania air in that particular way that only crisp money whispers, which is to say with the sound of something valuable changing hands for reasons that seem both perfectly obvious and completely insane.

The Henderson clan surrounds his makeshift betting window like shareholders at a particularly absurd board meeting. The hedge fund manager, let's call him Brad because of course his name is Brad, applies the same analytical intensity he usually reserves for parsing quarterly earnings reports to the baffling aerodynamics of wooden horse locomotion. Three generations, from iPad-wielding Emma to her grandfather who possesses that particular stillness that comes from having witnessed enough of American family life to know when not to comment, are momentarily united by shared financial interest in Horse Number Three.

Which is to say: they are literally betting on fake horses as a way of being together.

"Fewer folks on this one," Sammy observes with the sort of practiced neutrality that comes from decades of facilitating recreational gambling for people whose children attend schools that cost more than his annual salary. "Better odds, theoretically." He pauses, and in that pause lives the entire question of what we're actually doing here. "Now, Emma, are you playing hunch, or has Grandpa slipped you some insider information about Horse Number Three's aerodynamic quality?"

Emma, eight years old and already displaying the sort of analytical precision that suggests she'll one day grow up to either solve climate change or create the next financial crisis, squints at the painted steeds with the focus of someone conducting serious research. "Grandpa says Number Three has a certain aerodynamic quality."

Behind Sammy's chipped Formica counter, a Point of Sale system hums with the quiet efficiency of late capitalism, transforming hope and familial anxiety into trackable data points. The machine knows exactly how much the Hendersons are spending on this particular attempt at manufactured connection, though whether the machine understands what they're actually purchasing is another question entirely.

THE IMPOSSIBLE MATH OF AMERICAN TOGETHERNESS

Here's the thing about driving through Pennsylvania's Pocono Mountains in 2025: you'll encounter forty-three different establishments within a fifty-mile radius, each dedicated to the proposition that American families have become so fundamentally incompetent at enjoying each other's company that they require professional intervention. Not therapy, exactly. Therapy would be too honest about what's happening. Instead, we've created this vast economic ecosystem built around the fiction that what families need isn't help learning to connect, but rather the right environment in which their natural connecting abilities can flourish.

Which sounds reasonable until you consider that we're talking about billions, with a B, in annual revenue generated by teaching people how to do something that every other generation in human history figured out without a service industry.

The financial architecture here is genuinely stunning. Families pay upward of $200 per person per day for the privilege of having strangers orchestrate their spontaneity. Break that down and you're looking at roughly $40 per hour for professionally facilitated fun, which costs more than the median American hourly wage and approximately the same as most therapy sessions, except therapy at least admits you need help.

This is engineered authenticity at its most ambitious: the commodification of something so basic that until very recently it didn't occur to anyone that it could be commodified.

THE ARCHITECTURE OF ARTIFICIAL INTIMACY

To understand how this machinery actually operates, you need to witness something called Family Double Dare, which sounds like either a game show or a very specific type of psychological intervention, and which turns out to be both. Picture three hundred guests—many of whom have spent months planning this escape from their meticulously planned lives—about to be systematically covered in whipped cream, chocolate syrup, and the sort of calculated chaos that someone with a degree in Recreation Management has determined will optimize family bonding.

The premise is simple: strip away the careful choreography of modern family life by replacing it with a different, more deliberate choreography that pretends to be spontaneous.

So there I am, horizontal on slightly damp grass that smells like summer camp and institutional optimism, an empty ice cream cone balanced on my forehead like some sort of dessert-based meditation practice, while my son Ryan, who normally communicates primarily through Minecraft avatars and vaguely sullen acknowledgments, stands above me wielding chocolate syrup with the concentrated precision of someone attempting neurosurgery.

"Dad! Stop wiggling!" he commands, his voice carrying a authority I rarely hear during our regular interactions, which mostly involve me asking him to please put down his phone and him explaining why that's impossible right now. "You're disrupting the flow dynamics."

My sister-in-law documents this entire tableau on her iPhone, and later she'll post it with the caption "Utterly ridiculous," which manages to be both completely accurate and somehow beside the point. Because yes, it's ridiculous, but it's also the most focused attention Ryan has paid to me in weeks, and being waterboarded with chocolate syrup is a pyhrric victory in the larger war against whatever forces have made it so difficult for us to simply be present with each other.

THE ECONOMICS OF PURCHASED PRESENCE

The business model here, and this is where things get truly weird, is built on monetizing limitation rather than abundance. While luxury resorts compete on thread counts and celebrity chefs, family camps are selling exactly the opposite: fewer choices, forced proximity, and the radical proposition that maybe what American families need isn't more options but fewer.

It's the same economic principle that drives escape rooms, $35/hour for manufactured teamwork, corporate retreats, upward of $500/day for professional relationship facilitation, and dating apps, which charge you $40/month for the privilege of letting algorithms manage your emotional life. We've created entire industries around outsourcing the basic human functions that previous generations handled through what? Talking to each other? Spending time in the same room without entertainment? The very idea seems quaint and vaguely unrealistic.

The Kiesendahl family, who founded Woodloch Pines back when American families still possessed some vestigial ability to enjoy each other without professional guidance, built their entire operation around the mission of treating "each guest as company in our own homes." Not luxury but intimacy. Not amenities but authenticity. Though of course the authenticity is completely artificial, engineered by people whose job it is to make artificial things feel authentic.

David Morrison, a hedge fund manager whose presence here raises its own questions about what constitutes rational resource allocation, put it this way: "It's the only place we can actually relax as a family because someone else has taken over the logistical nightmare of modern life. At home, we mostly just argue about whose turn it is to empty the dishwasher."

THE GREAT AMERICAN OUTSOURCING PROJECT

Step back far enough and what emerges is the larger pattern: we've systematically transferred basic human capabilities to service professionals. Dog walkers handle companionship. Meal kit companies manage nutrition. Life coaches provide direction. Sleep consultants optimize rest. And now, family camp counselors facilitate bonding.

Each of these represents the same fundamental transaction: Americans paying other Americans to do things that Americans used to do for themselves, not because they can't, but because the skill set required to navigate modern life has somehow made these basic functions feel impossibly complex.

Federal Judge Robert Peterson's spectacular collapse during the camp Olympics illustrates the product being sold here. His usually composed judicial demeanor dissolved into helpless laughter as he and eight-year-old Emma became entangled in a three-legged race that ended with both of them horizontal in the grass, laughing in a way that his daughter later described as "the most he's laughed in months."

They didn't win. The winning wasn't the point. The point was that for approximately ninety seconds, a federal judge and his granddaughter shared the experience of being completely, ridiculously present with each other in a way that apparently requires professional facilitation.

THE MEMORY MARKETPLACE

Which brings us to the real question: what exactly are families purchasing here? Not connection itself—that would be too honest. Not even the skills needed to create connection—that would require admitting they lack those skills. Instead, they're buying something more subtle and possibly more troubling: the temporary experience of what connection feels like, preserved in Instagram posts and family stories, available for emotional replay during the months when actual connection feels impossible.

Sammy, counting bills at his betting window while the wooden horses continue their eternal, meaningless race, has watched this transaction repeat for four decades. The horses run, families laugh, children create memories of the time when everyone got along without trying. And then they return to their regular lives, where getting along requires constant effort and usually fails anyway.

The arrow leaves my bow, and I should mention that I have never successfully hit anything intentionally with an arrow in my entire life, in what physicists would generously describe as "a triumph of chaos theory over intentional marksmanship." It wobbles through the Pennsylvania morning air like a drunk hummingbird, defying several laws of physics, before somehow striking the hand-drawn Bigfoot target directly in what my nephew immediately announces to the entire archery range as "THE PEEPEE ZONE!"

Which is, come to think of it, a perfect metaphor for this entire industry: aiming for something important, missing completely, and somehow hitting exactly what you needed to hit, though you didn't know it at the time.

The real product being sold here isn't family bonding. It's the memory of what family bonding feels like. And in 2025, that memory alone is apparently worth billions.