This is a story about market inefficiencies, arbitrage opportunities, and the strange places where value hides in plain sight. From billion-dollar film franchises to frozen parking lots in Utah, from accidental modeling careers to the emerging AI economy, come along as we identify unlikely opportunities to shape the modern economy.

THIS ODD JOB

For a guy named Oddjob, there was nothing particularly odd about his gig. Harold Sakata's character in Goldfinger had perhaps the most straightforward job description in cinematic history: Personal bodyguard, manservant, and occasional bowler-hat-throwing assassin. The truly odd jobs belonged to Sakata himself – an Olympic silver medalist who pirouetted through careers as a professional wrestler before landing his iconic role as cinema's most well-dressed henchman.

FROM PRODUCE TO PRODUCER

Before the vodka martinis and elaborate stunts, before the gadgets and the girls, there was just a guy selling mushrooms from a cart in Manhattan's market district. The Broccoli family had already made history once – they'd introduced their namesake vegetable to America in the 1870s. But Cubby Broccoli hungered for something beyond the produce aisle.

VEGETABLE VENDETTA

His resume reads like a fever dream of odd jobs – jewelry assistant, casket maker, Hollywood gofer – until he spotted the opportunity that would change entertainment forever: the film rights to Ian Fleming's James Bond novels, available for a mere $50,000.

When every major studio passed on 007 as "too British," Broccoli didn't flinch. He partnered with Harry Saltzman and secured a modest $1 million budget from United Artists for Dr. No. The rest, as they say in both the produce and movie business, is history. The Bond franchise has since generated over $7 billion in box office revenue. Not bad for a guy who started out selling mushrooms.

The thing about odd jobs is they're only odd in retrospect. In the moment, they're just jobs – stepping stones, survival gigs, unexpected opportunities that might lead somewhere or nowhere.

WHEN KEEPING IT REEL GOES RIGHT

The gap between what things are and what they could be – that's where opportunity lives. Sometimes it's a vegetable vendor seeing the cinematic potential in a British spy novel. Sometimes it's a brand realizing that imperfection sells better than perfection. And sometimes, as I discovered, it's about being in exactly the right place at exactly the right time, even if that place is a Miami beach wearing someone else's clothes.

ACTOR SLASH MODEL

While on vacation in Texas, one of the greatest states in the union and the only state with its own power grid. Chubbies, the irreverent bathing suit brand known for its thigh-liberating shorts and clever marketing, slid into my inbox with a request for models in the Miami area. At best I am a part-time picture frame model but Chubbies was after something far more valuable in today's authenticity-obsessed market: real people who could make their clothes look, well, real. The kind of people who might wear sky-blue shorts with tiny flamingos while grilling burgers or playing cornhole.

CASTING CALL TO ACTION

My wife, demonstrating the kind of wisdom that probably explains why she married me in the first place, posed a simple question: "What's the worst that could happen?"

Twenty minutes and one cowboy hat selfie later, I had submitted my application. To my surprise – and probably theirs – they responded.

THIGH TIMES IN MIAMI

Standing in a makeshift outdoor green room overlooking the ocean, watching families cycle through photo shoots while trying to convince myself that my "bold shirt" choice was somehow strategic rather than desperate.

The space had the controlled chaos of a well-organized circus, complete with wardrobe racks, nervous participants, and the constant hum of professional equipment being wheeled around. Everyone was busy except the talent, that is until they get the call.

"You're up," called a production assistant, clipboard in hand. I followed her past the equipment cases and light stands for the "elevated short shoot" – a term I pretended to understand while nodding with the conviction of someone who definitely knows what they're doing.

My brief moment in the sun wasn't over yet. Like a substitute player unexpectedly thrust into the fourth quarter of a championship game, I found myself being called back to set again for a group beach football shoot. Except by the time they were ready for me, I was nearly out of time. In a plot twist worthy of a telenovela, the director pivoted and cast me in a surfboard shoot instead. Nothing says "authentic brand representation" quite like watching a finance guy try to look natural with a surfboard under his arm.

FROM BLUE STEEL TO REAL DEAL

Between takes, I found myself part of an unlikely community. There was the contractor dad, channeling his inner Zoolander with surprising commitment. The mom who chaperoned her kids through their popsicle shoot but refused to step in front of the camera herself. We were all amateurs, all slightly confused about how we got there, all trying not to look like we were trying too hard.

In the end, that's what made it work. Chubbies wasn't looking for Blue Steel or perfect jawlines. They wanted authentic moments, genuine laughs, and the kind of natural awkwardness that comes from putting regular people in irregular situations. They wanted real people wearing real clothes, doing real things.

It's a fascinating economic model when you think about it. Instead of paying premium rates for professional models, brands like Chubbies tap into a vast reservoir of willing amateurs who bring authenticity to their marketing. We're living in an age where being relatable is more valuable than being perfect, and your neighbor's Instagram might carry more influence than a billboard in Times Square.

DADDY MADE WHISKEY AND HE MADE IT WELL

There's something deliciously ironic about Utah's relationship with alcohol. In a state where all liquor stores are government-owned, they've inadvertently created one of America's most fascinating underground economies.

Here's how it works: Every third Saturday of the month, Utah's state liquor stores release their allocated bourbon inventory. For the uninitiated, allocated bourbon is the unicorn of the spirits world.

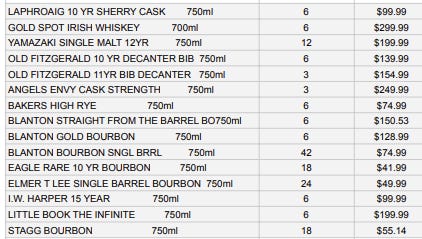

These aren't your everyday bottles that line the shelves at the local liquor store.

These are the ones that bring out the bourbon "taters" - bourbon enthusiast who are considered overly enthusiastic or "showy" about their whiskey collection, often buying bottles based on hype or perceived prestige rather than the actual quality of the drink. These bottles often end up behind glass cases or, more likely, on secondary market websites like caskers at nosebleed markups

LIQUID ASSETS

As luck would have it, my Utah visit coincided with the third Saturday, and as both a bourbon enthusiast and a student of market inefficiencies, it was game on. Grabbing three friends we set out at 10:45 AM on a Saturday, as we got closer to the store I realized a lot of people had the same idea. First there was no parking. The line stretched three times longer than expected – 150 people deep, all shivering with anticipation in just above-freezing temperatures. . After all, nothing warms the soul quite like the prospect of snagging a bottle of Buffalo Trace Antique Collection at MSRP.

The doors opened at 11 and one of the first customers emerged from the store, only to smoothly pivot back into line – a move that would've gone unnoticed if Utah's icy sidewalks hadn't had other plans. His feet betray him, creating an unplanned performance piece on the hazards of winter bourbon hunting.

At this point, it was apparent that while many were solo hunters, others operated in coordinated teams who had turned waiting in sub-freezing temperatures into a profitable arbitrage opportunity. The man who fell handed his bottle to another gentleman exiting the store. Proving he was a professional line stander who gets paid per bottle secured.

Inside, the scene is a masterclass in controlled chaos. A line snaked through the aisles, leading to a folding table where an older woman stood over a list printed on the table. Certain items are already crossed out – casualties of the first wave of buyers. It's a reminder that in the bourbon game, as in life, timing is everything.

PROOF OF WORK

Our crew of four manages to secure our allocated treasures – a collection of bottles that will either become prized additions to our bars or lucrative entries on the secondary market. This is where the real economics kick in. That $60 bottle of Weller 12? It's going for $400 online. The $100 E.H. Taylor? Try $800. The arbitrage opportunity is clear enough that some people make a living just standing in lines like this.

The irony isn't lost on me: Utah, the state where Brigham Young once declared that whiskey should only be used to wash wounds and bathe lambs, has become a key node in America's bourbon arbitrage network. The very restrictions meant to control alcohol sales have created something more intoxicating than mere liquor, a thriving grey market.

That's the thing about markets – they're just stories we tell ourselves about value.

Whether it's crypto or bourbon, Pokemon cards, or Picassos, the underlying mechanics are the same: scarcity, desire, and the endless human capacity to turn anything into a trade. And somewhere in Kentucky, in a rick house that probably hasn't changed much since prohibition, another barrel is aging, blissfully unaware of the elaborate dance it may inspire when its contents finally find their way to a Utah parking lot on a cold Saturday morning.

Markets evolve, but arbitrage remains constant.

While bourbon hunters brave the Utah winter for physical bottles, a new generation of opportunity seekers is discovering similar inefficiencies in the digital realm. The same principles that turn a $60 bottle of Weller into a $400 resale apply to the gap between AI's capabilities and human understanding. Instead of limited releases and state regulations, we're dealing with limited knowledge and technological barriers. The arbitrage opportunity has simply moved from atoms to algorithms

PROMPTS AND CIRCUMSTANCE

Remember when the strangest job title you could have was “Social Media Influencer”? Those were simpler times. Today, we're watching the birth of career paths that sound like they were pulled from a William Gibson novel: AI Prompt Engineer, Machine Learning Ethics Officer, Robot-Human Interaction Designer. The future of work isn't just coming – it's being generated at 1,000 tokens per second.

But here's where things get interesting. We're not just creating new jobs; we're fundamentally reimagining what a "job" even means. Take the rise of AI agents – autonomous digital workers that can handle everything from scheduling meetings to writing code. They're not replacing humans so much as creating a new economic layer where human creativity becomes the ultimate arbitrage opportunity.

Consider this: In a recent experiment, a team of AI researchers created what they called an "agent marketplace" – imagine if TaskRabbit and ChatGPT had a baby that went to business school. They watched as digital agents began spontaneously forming micro-economies, trading services and resources with an efficiency that would make Adam Smith blush.

The implications are staggering. We're moving from a world of finite jobs to one of infinite tasks, where work isn't bound by traditional roles but flows freely between human and artificial intelligence. It's like watching the evolution of labor in fast-forward, except instead of moving from agriculture to industry, we're leaping from structured employment to what can only be described as economic jazz – improvised, collaborative, and occasionally chaotic.

DIGITAL LABOR PAINS

This isn't just theoretical. Right now, people are making real money as "AI Whisperers" – professionals who know how to speak both human and machine, translating business needs into precise prompts that get results. Others have become "Dataset Curators," the sommeliers of the AI world, ensuring that our artificial colleagues develop a refined palate for information rather than gorging themselves on junk data.

The beauty of this shift is its democratizing nature. You don't need a PhD in computer science to participate in the AI economy. You just need to understand the new language of opportunity. It's less about what you know and more about how creatively you can connect dots that others don't even see exist.

As I write this, someone somewhere is probably inventing a job title that won't make sense until next Tuesday. And that's exactly the point. We're no longer in the business of filling positions – we're creating them in real-time, responding to needs that emerge from the dynamic dance between human ingenuity and artificial capability.

Because here's the thing about the future of work: it's not about humans versus machines. It's about humans and machines versus the problems we want to solve. And in that equation, the odd jobs of today are just beta tests for the normal jobs of tomorrow.

CTRL+ALT+OPPORTUNITY

What if the best job you'll ever have doesn't exist yet? Not in the "we haven't invented it" sense, but in the "you haven't invented it" sense.

The beauty of market inefficiencies is that they're never static. As soon as one arbitrage opportunity closes, another opens. And right now, the biggest opportunity gap in history is forming between what artificial intelligence can do and what humans understand it can do.

The thread that connects a mushroom vendor to a billion-dollar franchise, that links a state-run liquor store to a thriving grey market, that turns regular people into brand ambassadors, is simple: the ability to see value where others don't. It's about developing what I call "arbitrage thinking" – the skill of spotting the gap between what something is worth and what people think it's worth.

Here's the framework:

Look for Friction: Where are people struggling? What processes seem unnecessarily complicated? Friction is often a sign of market inefficiency.

Find the Hidden Value: What resources or capabilities are being underutilized? What skills or assets could be repurposed?

Connect Unexpected Dots: The biggest opportunities often lie at the intersection of seemingly unrelated fields. What happens when you combine AI with coffee roasting? When you mix government regulation with bourbon collecting?

Act Fast, Learn Faster: The window for arbitrage opportunities is often short. The key isn't to wait for the perfect opportunity but to recognize and act on good ones quickly.

THE FUTURE IS EASY TO PREDICT WHEN YOU ARE THE ONE MAKING IT

The future belongs not to those who can predict it, but to those who can spot its inefficiencies. Whether you're a vegetable vendor dreaming of Hollywood, a finance guy accidentally modeling swimsuits, or an entrepreneur exploring the frontiers of AI, the principle remains the same:

The odd jobs of today are just the billion-dollar industries of tomorrow, waiting for someone weird enough to see their value.

The gap between AI's capabilities and human needs isn't just a market inefficiency; it's an opportunity waiting for someone weird enough to spot it and brave enough to seize it.

And somewhere right now, someone is looking at their current situation – their skills, their knowledge, their position – and seeing not what it is, but what it could be. That person might even be you.